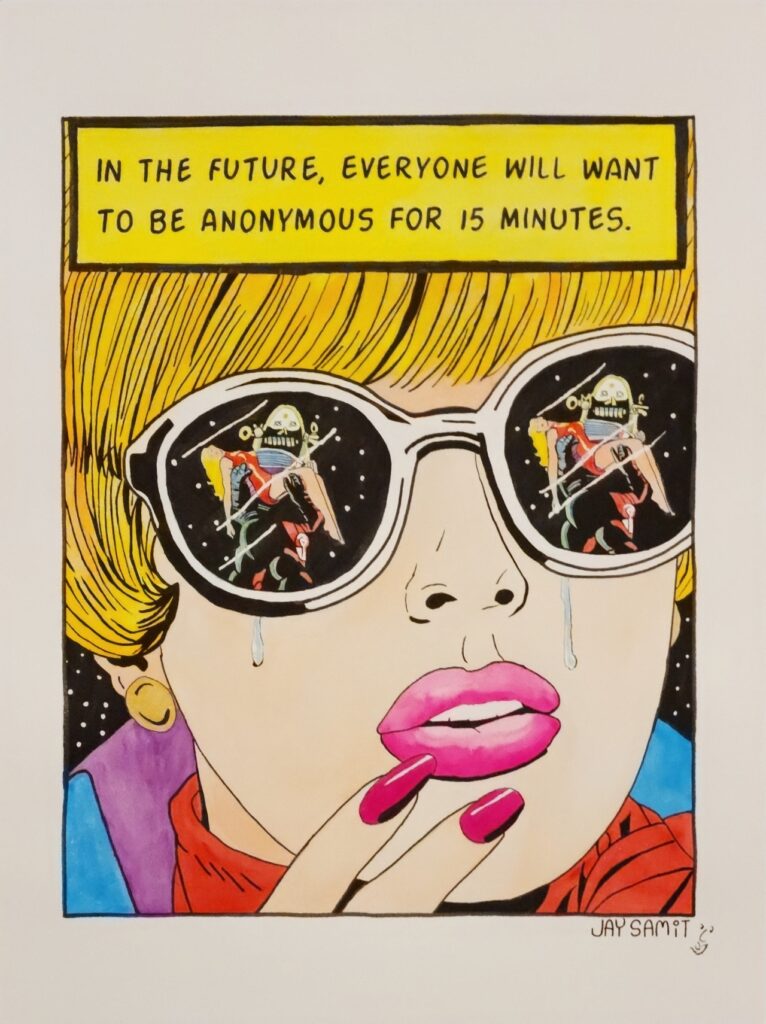

In 1968, when Andy Warhol proclaimed that “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes”, he couldn’t have imagined a world where unplugging and becoming anonymous would become a luxury. We look at our phones before our feet touch the floor in the morning, stare at screens all day, have disembodied voices guide us through traffic, interact with corporate chatbots on the phone and then curl-up at night with our tablets, TVs, and phones as our contestant companions. Facebook, Google, Tinder, Netflix, and Alexa now dominate the very lives they were intended to enhance. Beauty filters change how others see us and how we see ourselves. This dichotomy, the tension between technology and humanity, is explored in a fresh new way through the 50 paintings being exhibited at Jay Samit’s new solo show at the Richard Taittinger Gallery in New York.

In previewing Samit’s first post-pandemic show, one immediately confronts the realities of modern life. The interplay between familiar comic book imagery and penetrating text takes the viewer on a dystopian journey of the information age. Where the Pop Art movement grew out of the optimism of and consumer-centric culture of post-World War II England and America, Samit’s watercolors emerged from his own reflections of his forty-year career in technology and the new world he helped create.

Samit was first exposed to the Internet while a student at UCLA in the 1970s and spent the following decades pioneering the very technologies we now take for granted. He first put video on personal computers in the 1980s and built the first million-member college social network in the 1990s. At the dawn of the new millennia, Samit worked with the White House to get the Internet into every classroom in America. His hope was that the so called “information superhighway” would disseminate knowledge more broadly and equitably. He saw the Internet as a tool for providing equal access to education globally and making the people of the world more connected to each other. In senior management roles at companies such as EMI, Universal Studios, and Sony, he expanded entertainment’s reach around the world by creating download and streaming services. By all accounts, Samit should be looking fondly back at the body of his technological achievements, but to paraphrase Jurassic Park’s Dr. Ian Malcolm, “He was so preoccupied with whether he could do these things, that he didn’t stop to think if he should.”

The pause of the Pandemic gave Samit time to meditate on the dark side of technology. He saw how ever more powerful artificial intelligence was enslaving us. Much like the frogs that don’t jump out of the pot as it boils, we were so busy using the latest and greatest apps, we didn’t notice how our humanity was reaching its boiling point. Pop Culture is no longer a mass media shared experience, but rather an all too alienating private interaction between humans and their all too pervasive devices. Artificial Intelligence and algorithms manipulate how we live, love, work, and think. AI influences who we date, what we consume, watch, and even what we believe to be true. Our reality is an amalgamation of pixels. The promise of social media making us each more connected has been swiftly coopted to be engines for hate and divisiveness. Social media’s promise of empowering the Arab Spring has devolved into a monopolistic totalitarian tool. Advertising platforms that Samit built to engage are now used to target our vulnerabilities and exploit our insecurities.

Artist Jim Dine exclaimed that Pop Art “is the American Dream, optimistic, generous and naïve.” The vibrant mass consumerism first exhibited at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1962, which showcased works by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, is a launch pad for Samit’s unabashed art. Based in California, Samit’s work is influenced by fellow Los Angeles artists such as Ed Ruscha, Joe Goode, Phillip Hefferton, Wayne Thiebaud, and Robert Dowd. Whereas the Pop Art from half a century ago highlighted how the products of everyday lives had become commodities to be bought and sold,

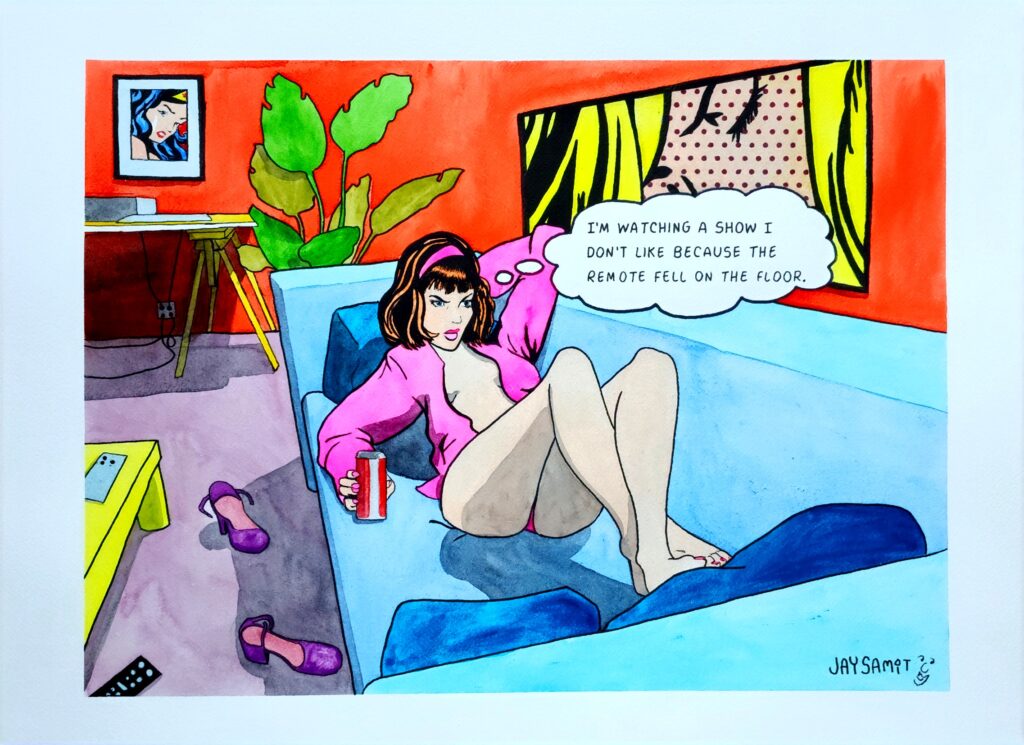

Samit’s collection of paintings shine the spotlight on how we have become the commodities. Our lives reduced to pixels of data sold to the highest bidder millions of times every day. What further separates Samit’s art, and this exhibition in particular, from the traditional Pop Art movement is how personal each painting feels. We identify with the frustrations of screaming “representative” into the phone and relate to the woman who ponders, “I’m not sure if Tinder is broken or I’m just ugly.” The centerpiece of the show is a bright 18” x 24” tryptic saturated in yellow, orange and magenta. Across three ever tightening close-ups, a woman cries out in agony, “Alexa, turn my feelings off.”

Once we look up from our devices, we see our unvarnished selves. By exploring the value exchange we all have succumbed to: trading privacy for convenience, intimacy for popularity, and true connections for likes, Samit’s works invite us all to reflect on what our lives have become and what we have all lost along the way.

Samit’s painting technique of precisely conveying the aesthetic of last century’s mass-produced comic books lures the viewer into each familiar vignette only to be confronted by biting text that alters the context of the imagery. Each of Samit’s paintings have a poignancy that take us on this journey from past to present, from complacency to abhorrence, with a wink and a nod that will often have you laughing out loud. This exhibition is also a rune stone for future historians to be able to look at what life was truly like at the beginning of the 21st century.

All of Samit’s watercolor and gouache works are painted on 140 lb 100% pure cotton paper. Paintings range in size from 12” x 16” to 18” x 24” and are priced from $5,000 to $7,500. Dots & Pixels runs now through December 4th at the Richard Taittinger Gallery at 154 Ludlow Street New York City.

0 comments on “Dots & Pixels: Pop Art Reflections of Our Digital Lives”